Members’ Dinner Thursday, February 14, 7–9 p.m.

Annual Business Meeting

Friday, February 15, 12:30–1:30 p.m.

New York Hilton Midtown, 4th Floor, Harlem Room

Members are encouraged to attend.

Sponsored Session:

“Women Artists in Germany, Scandinavia, and Central Europe, 1880-1960”

Saturday, February 16, 10:30 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

New York Hilton Midtown, 2nd Floor, Gramercy West

Chaired by Kerry Greaves. Papers by Emil Leth Meilvang, Nora Butkovich, Lauren Hanson, and Lynette Roth. See: https://caa.confex.com/caa/2019/meetingapp.cgi/Session/1607

Member Papers

Special Event:

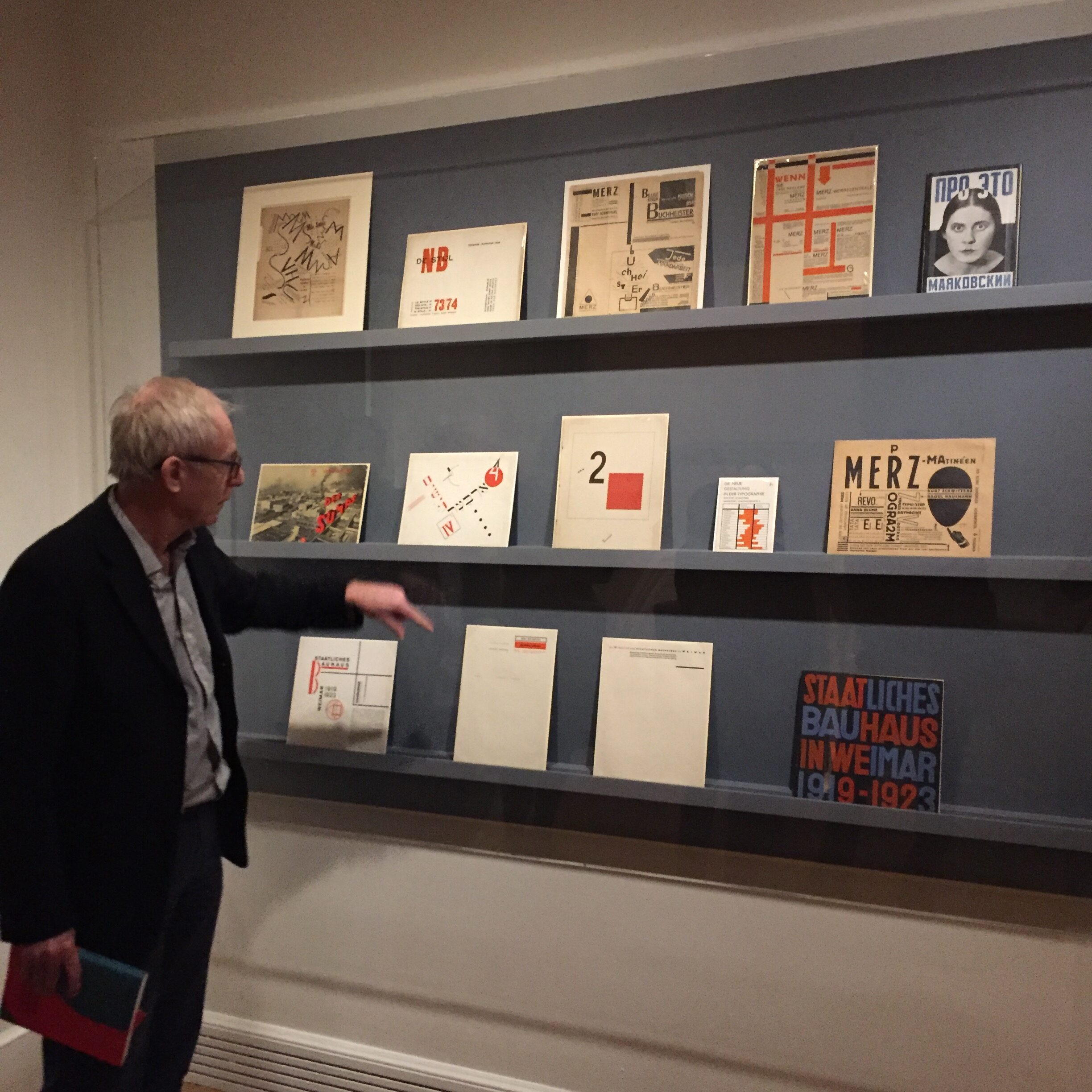

Curator’s Tour of “Jan Tschichold and the New Typography”

Sunday, February 17, 11:00 a.m.–12 p.m.

Bard Graduate Center Gallery, 18 West 86th Street, New York, NY 10024

Praise for the HGSCEA panel chaired by Allison Morehead from the Association for Critical Race Art History (ACRAH)

106th College Art Association Annual Conference

Los Angeles, February 21–24, 2018

HGSCEA Session

Saturday, February 24, 2018, 2–3:30

Los Angeles Convention Center, room 501A

Critical Race Art Histories in Germany, Scandinavia, and Central Europe

Rebecca Houze, Northern Illinois University,

“Cultural Appropriation and Modern Design: The Art Colony at Gödölló in Critical Perspective”

Patricia G. Berman, Wellesley College,

“Whitewashing Whiteness in Nordic ‘Vitalism'”

Bart Pushaw, University of Maryland,

“Visual Reparations: Scandinavian Privilege and the Discontents of Nordic Art’s Colonialist Turn”

Kristin Schroeder, University of Virginia,

“From Sideshow to Portrait: Looking at Agosta, the Pigeon-Chested Man and Rasha, the Black Dove (1929)”

Critical race theory, which entered art history through postcolonial analyses of representations of black bodies, has remained relatively peripheral to art historical studies of Germany, Scandinavia, and Central Europe, whose colonial histories differ from those of countries such as Britain, France, and the United States. At the same time, art historical examinations of white supremacy in the Nazi period are frequently sectioned off from larger histories of claims to white superiority and privilege. Centering critical race theory in the art histories of Germany, Scandinavia, and Central Europe, this panel will consider representations of race in the broadest of terms — including “white makings of whiteness,” in the words of Richard Dyer. We invite papers that together will explore the imagination and construction of a spectrum of racial and ethnic identities, as well as marginalization and privilege, in and through German, Scandinavian, and Central European art, architecture, and visual culture in any period. How have bodies been racialized through representation, and how might representations of spaces, places, and land — the rural or wilderness vs. the urban, for instance — also be critically analyzed in terms of race? Priority will be given to papers that consider the intersections of race with other forms of subjectivity and identity.

HGSCEA Members at CAA 2018

Peter Chametzky,

“Space, Time, and Motion in Maziar Moradi’s Ich Werde Deutsch”

Session: Time, Space, Movement: Art between Perception, Imagination, and Fiction

Saturday, 2-3:30 p.m., Room 406A

Sabine Eckmann

Co-Chair

Session: International Abstraction after World War II: The US, France, Germany, and Beyond”

Wednesday, 8:30-10:00 a.m., Room 410

Eva Forgacs

“The 1968 Prague Spring in Central Europe. Art and Politics”

Session: ’68 and After: Art and Political Engagement in Europe

Thursday, 2-3:30 p.m., Room 409A

Peter Fox

“Germanizing Intarsia c. 1900”

Session: Material Techniques in the Cultural Sphere

Wednesday, February 21, 8:30 – 11 AM. Room 409B

Susan Funkenstein

“Visualizing Dance in the Third Reich: Gender, Body, … Modernity?”

Session: Modernity, Identity, and Propaganda

Saturday, 10:30 a.m.-12:00 p.m., Room 501B

Tomasz Grusiecki

“Of Mixed Origins: Tracing Michał Boym’s ‘Sum Xu’”

Session: Archives, Documents, Evidence

Wednesday, 2-3:30 p.m., Room 409B

Charlotte Healy

“Knotted, Woven, Unraveling: Fabric as Structure in the Work fo Paul Klee”

Session: Structure, Texture, Facture in Avant-Garde Art

Saturday, 4-5:30 p.m., Room 501A

Juliet Koss

Discussant

Session: Avant-Gardes and Varieties of Fascism, Part II

Friday, 10:30 a.m.-12 p.m., Room 407

Max Koss

“The Intimacy of Paper: Fin-de-siècle Print Culture and the Politics of the Senses”

Session: Intimate Geographies

Thursday, 4-5:30 p.m., Room 410

Megan Luke,

“Books of Stone”

Session: Avant-Gardes and Varieties of Fascism, Part I

Wednesday, 2-3:30 p.m., Room 501A

Bibiana Obler

“A Strip of Red Velvet”

Session: Warp, Weft, World: Postwar Textiles and Transcultural Form

Friday, 8:30-10:00 a.m., Room 408B

Dorothy Price

Association for Art History/Art History/Wiley Publishing reception

Thursday, 5:30 pm, Santa Anita-A Room, Lobby Level, Westin Bonaventura Hotel

Jeannette Redensek

“Cool, brittle, luminous, clear: Josef Albers and the materiality of glass at the Bauhaus”

Session: Structure, Texture, Facture in Avant-Garde Art

Saturday, 4-5:30 p.m., Room 501A

Nathan Timpano

“Blue Horse, Yellow Cow: Franz Marc, Romanticism, and the Color of Theosophy”

Session: Interaction with Color Redux

Saturday, 10:30 a.m.-12 p.m., Room 402B

James van Dyke

“The Vulgarity of Otto Dix’s Facture”

Session: Structure, Texture, Facture in Avant-Garde Art

Saturday, 4-5:30 p.m., Room 501A

Greg Williams

“Practice Situations: Franz Erhard Walther and the Pedagogical Impulse”

Session: No Experiments: Art, Culture, and Politics in the Federal Republic of Germany, 1949-1989

Wednesday, 10:30 a.m.-12:00 p.m., Room 410

Andres Zervigon

Discussant

Session: Avant-Gardes and Varieties of Fascism, Part I

Wednesday, 2:00 p.m.-3:30 p.m., Room 501A

Historians of German Scandinavian and Central European Art and Architecture (HGSCEA) Sponsored Sessions:

Revivalism in Twentieth-Century Design in Germany, Scandinavia, and Central Europe, Part I

Date and Time: Friday, 02/17/17: 3:30–5:00 PM, Nassau Suite-East/West, 2nd Floor

Chair: Paul Stirton, Bard Graduate Center

Christopher Long (University of Texas at Austin) Adolf Loos, Oskar Strnad, and the Biedermeier Revival in Vienna

Charlotte Ashby (Birkbeck, University of London) National – Regional – International: The City Halls of Copenhagen, Stockholm and Oslo

Juliet Kinchin (Museum of Modern Art) The Neo-Baroque, the ‘Folk Baroque’ and Art Deco in Central Europe

Erin Sassin (Middlebury College) The Biedermeier Revival: Artisans, and Ledgenheime

Revivalism in Twentieth-Century Design in Germany, Scandinavia, and Central Europe, Part II

Date and Time: Friday, 02/17/17: 5:30–7:00 PM, Nassau Suite-East/West, 2nd Floor

Chair: Paul Stirton, Bard Graduate Center

Room: Nassau Suite East/West, 2nd Floor, New York Hilton Midtown

Dragan Damjanović (University of Zagreb) Neo-Historicism in Croatian Architecture of the first Half of the 20th Century

Marija Dremaite (Vilnius University) The Folklorist Revival within Soviet Modernism in the Baltic Republics in the 1970s

Hedvig Mårdh (Uppsala University) Translating the Gustavian: Heritage Consumption and National Aesthetics in Sweden

Anni Vartola (Aalto University, Finland) Eclectic regression? Revivalist phenomena in postmodern Finnish architecture

There’s No Such Thing as Visual Culture

Wednesday, February 3

Chair: Corine Schleif (Arizona State University)

Visual display, the gaze, and scopic economies have played important roles in the consideration of German art. Yet visual perception never existed in isolation. In fact, neuroscience demonstrates interactions of many sensibles with respect to cognition, emotion, and memory. Presenters in this session might observe how the visual was augmented, diminished, or contradicted by the interplay of other senses. They might analyze how museum practices have feminized objects by subjugating them through the aestheticizing gaze, thereby foreclosing more interactive sensualities. Participants might theorize liturgical processions, public Heiltumsweisungen, theatrical Gesamtkunstwerke, popular reenactments, or documentary reproductions. Why did our discipline develop as pursuant of the visual? How did early German and Central European art historians support or resist purely visual regimes? Why did the “haptic” gain consideration in German art historiography? What might scholarly production learn either from cinematographic attempts to engage the entire sensorium or from journalistic practices voluntarily limiting visual representation of sensitive material?

Charting Cubism across Central and Eastern Europe Friday, February 13 at CAA and Saturday, February 14 at the MET Museum

This symposium consists of a CAA session sponsored by HGCEA and a related session co-organized by HGCEA and the Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Chairs: Anna Jozefacka, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Hunter College, City University of New York and Associate Curator, Leonard A. Lauder Collection, New York, and Luise Mahler, Assistant Curator, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Keynote speaker: Prof. PhDr. Vojtěch Lahoda, Director, Institute of Art History, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Prague

Respondent: Éva Forgács, Adjunct Professor, Liberal Art and Sciences, Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, CA

The impact of Cubism on twentieth century art was instant, widespread, and long lasting. Participating in the Cubist circles were artists and intellectuals from various backgrounds, including a large contingent from Central and Eastern Europe. The cultural exchange between this vast geo-political region and Paris – facilitated by the networks of artists, dealers, collectors, critics, and scholars – culminated in contributions that are integral to the theoretical implications of Cubism. Building on the growing scholarship on the region’s artistic avant-gardes, this two-part symposium investigates two inter-related questions. The first concerns ways in which Cubism was integrated into the cultural scenes of the various nations, as it was here that Cubist language diversified and crossbred with approaches to visual form previously unconsidered. The second investigates strategies used by artists, critics, and scholars from these European regions that aided them in asserting their participation in the Cubist movement and the surrounding discourse, both at home and abroad, and by so doing internationalized the movement. As Cubist scholarship begins to address the movement’s global influence, Charting Cubism considers the specificities of the interaction and engagement with Cubism in Central and Eastern Europe, and evaluates how local artists, dealers, collectors, critics, and scholars partook in its growth and evolution.

The papers presented in the first part of the symposium examine the Czech journal Umělecký měsíčník (Arts Monthly), the adoption of Cubism in Latvia post-1918 independence, and the complicated case of Hungarian Cubism. In the second part of the symposium papers delve into the reception of Cubism in the region by focusing on Czech art historian and collector Vincenc Kramář, Ukrainian painter and theorist Oleksa Hryshchenko (Alexis Gritchenko), and Cold War era Soviet art criticism and theory.

First Session:

“Platform for Czech Cubism – the journal Umělecký měsíčník (Arts Monthly)”

Vendula Hnidkova, Ph.D., Institute of Art History of the Academy of Sciences, Prague

In 1911, a group of young Czech avant-garde artists founded an association named Skupina výtvarných umělců. Interested in Cubism, they rapidly ascended as the style’s most influential agents. Their published journal Umělecký měsíčník (Arts Monthly), maintained two objectives: to create a platform for Cubist art, ideas, and theories within Czech culture, and to propagate and popularize local art abroad. The magazine’s editors intended to publish a German and French edition employing regional collaborators and correspondents, among them Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Adolphe Basler, and Guillaume Apollinaire. This paper will analyze the editors’ personal contacts and networking strategies as well as their particular relationships with various artistic localities. Such analysis will allow for an investigation of the journal’s impact on the reception of Cubism in the region before World War I, and the role of Czech Cubist artists on the international art scene.

“Latvian Cubists, Table for Six…”

Mark Allen Svede, Senior Lecturer, Department of History of Art, The Ohio State University

By late 1918, Latvian political independence was declared, and native modernists sought similar autonomy. The expressionism they explored during the war years was soon exchanged for Cubism, and in Rīga the ascendancy of this style was startlingly swift. The newly formed art museum acquired Cubist works for its collection, grants for travel abroad from a cash-strapped government were awarded to modernists more frequently than to traditionalists, and Cubist maquettes were in such serious contention for national monument design concourses that these competitions were suspiciously, repeatedly interrupted. Cubism’s penetration of public consciousness was such that a popular café named “Sukubs,” a portmanteau of “Suprematism” and “Cubism,” opened in Rīga. The conspicuous success of these progressive artists rankled traditionalists, and critical attacks upon the Cubists soon bore the epithet “sukubisms.” This mutual antagonism escalated to spectacular levels, in the press and in the courtroom, on gallery walls and on snowy cobblestone streets.

“Known and Unknown Hungarian Cubists”

Gergely Barki, Art Historian, Advisor of 20th Century Art at Szépművészeti Múzeum – Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest

In around 1910, when the spirit of Cubism was predominant in Paris, a young generation of Hungarian artists arrived in the French capital and engaged with this new pictorial language. While a number of them exhibited alongside the style’s original creators, their art appeared only sporadically and exerted less influence at home. Although Hungarian artists produced Cubist work, its near non-existence in Hungary at the time did not allow for a unified Cubist group to develop. Only few works created by older Hungarian painters who had returned to Budapest from Paris after 1906 to 1908 (primarily importing Fauvism and Cézanne-ism) showed Cubist tendencies. Instead, members of the younger generation living in Paris formed a Hungarian Cubist diaspora in Paris. Yet, due to the outbreak of World War I the majority was forced to stay abroad and unable to continue their work and participate in the spread of Cubism in Hungary.

Second Session:

“Picasso, Braque and Kramář: The Czech Reception of Synthetic Cubism”

Nicholas Sawicki, Assistant Professor of Art History, Department of Art, Architecture and Design, Lehigh University

Between 1912 and 1914, Picasso and Braque experimented with a range of new materials and techniques that dramatically shifted the direction of Cubism, towards what is often described as its “synthetic” phase. Garnering mostly limited interest from buyers and audiences at the time, these works attracted unique attention from Vincenc Kramář, the Czech collector and historian of Cubism. Kramář viewed them during his travels to Paris and made several purchases for his collection. On his interpretation, this newest body of work marked an important turning point for the two artists: an innovative use of pictorial fragments, truncated lettering and manufactured materials that introduced to Cubism a new “quality of reality,” while definitively breaking with the traditions of conventional representation. Drawing on Kramář’s private and published writing, this paper examines his evolving understanding of Picasso’s and Braque’s 1912 to 1914 production, and its echoes in the Czech artistic community.

“A Crisis in Cubism: The Theoretical Writings of Alexis Gritchenko”

Myroslava M. Mudrak, Professor Emerita, The Ohio State University

During the critical decade of Cubism’s expansion (1908-1918), the Ukrainian painter and theorist, Oleksa Hryshchenko (Alexis Gritchenko) who first encountered Cubism in Paris in the 1910s, helped mitigate the indiscriminate adoption of Cubist aesthetics by Eastern European artists by empowering them to recognize and incorporate local traditions, such as the Byzantine, and by so doing render abstraction accessible to the public. In his major tracts of 1912 and 1913, Hryshchenko promoted modern painting’s transubstantiation of the object into an absolute, an act meaningful to viewers habituated to scrutinizing icon images. In his 1917 essay, “The ‘Crisis of Art’ and Contemporary Painting” Hryshchenko identified an existential dilemma in Cubist art brought on by what Paris-based, émigré philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev described as “dematerialization” within Cubism, as well as an ensuing threat of alienation from viewers, a dilemma to be played out in Eastern European modernist painting of the interwar period.

“Cubism and Soviet Art Criticism during the Cold War”

Kirill Chunikhin, Ph.D. Candidate at Jacobs University Bremen, Germany, and Terra Foundation Pre-doctoral Fellow, The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Although Cubist art was rarely exhibited in the U.S.S.R. during the Cold War, dozens of Soviet authors wrote on the subject. Cubism was afforded no exemption from the hostility directed toward all of Western avant-garde art by Soviet art criticism, with the movement described as formalist, anti-humanistic, and bourgeois. However, the voices critical of Cubism were not monolithic. While one is hard-pressed to find official apologies for Cubism during the Cold War, the intellectual arguments and tone of critical discussion of Cubism vary. The paper will focus on different theories of Cubism within Marxist-Leninist aesthetics and on the ways those theories served one common purpose—reproducing the official negative stance on modernism.

Popularizing Architecture

Chair: Wallis Miller (University of Kentucky)

Popularizing Architecture will focus on the dissemination and circulation of new ideas in architecture to non-professional audiences in Germany and Central Europe since the late nineteenth century, when publications that included architecture began to emerge in large numbers. Over time, architectural exhibitions, film, radio, television, and the Internet joined newspaper and magazine articles to form a complex media landscape that continues to address a wide range of audiences today. Recent research on architecture and media has been primarily concerned with professional contexts, examining case studies focusing on Western Europe and the United States. The session will shift this regional focus to Germany and Central Europe to examine more explicitly the relationship between architectural proposals—theoretical or built, traditional or innovative—and non-professional audiences while also exploring the concept of popularization. Papers on a range of places and periods since the mid-nineteenth century will attend to the following questions: How did non-professional audiences encounter new ideas about architecture? How did this experience diverge from that of professional architects? To what extent did the dissemination of architectural ideas exploit new media? How might a regional focus on Germany and Central Europe prompt particular questions and conclusions regarding architecture and its popularization?

“The Viennese Interior and its Media”

Eric Anderson, Rhode Island School of Design

Vienna in the 1870s was a city transformed not only by the monumental architecture of the Ringstrasse but also by popular interest in interior decoration fed by a nascent media culture of design. Artists and tastemakers employed a variety of techniques to promote home decoration to a growing middle-class audience. This paper presents four media—a book, a museum, an “ethnographic village,” and an artist’s studio—and poses questions about the mechanisms through which meanings accrued around interiors. How did various media facilitate unique forms of spectatorship? Who consumed these representations? How did meanings vary among different formats and audiences? At stake in these questions are insights into not only the cultural history of Vienna, but also our own, heavily mediated experience of design, in which publications, museums, and trade fairs continue to shape meaning in ways both powerful and too often taken for granted.

“’Building Unleashed’: Building as public discourse in the 1929-30 Bauhaus traveling exhibition”

Dara Kiese, Pratt Institute

The 1929-30 Bauhaus traveling exhibition was Hannes Meyer’s opportunity to showcase the school’s new approach and accomplishments during his tenure as second director. Publicity, sales and advancing ties to the manufacturing industry were main objectives, but Meyer’s ambitions were greater. This paper considers the exhibition as a springboard for public discourse and user interaction about the built environment through installations, exhibition catalogues, lectures, publications and press coverage. With a focus on theoretical architectural student studies and multidisciplinary practices and methodologies, the exhibition cultivated a new relationship between architect and visitor/consumer/user, in which the end users played an active role in the design and interpretive processes. Current Bauhaus pedagogical principles and designs equipped the public sphere with discursive and practical tools necessary to imagine and create individualized, sustainable environments—building unleashed.

“‘You are Now Entering Occupied Berlin’: Architects and Rehab-Squatters in West Berlin”

Emily Pugh, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts

In the 1970s and 1980s, the West Berlin neighborhood of Kreuzberg formed the center of a movement that brought architecture professionals together with political activists and squatters to reform urban housing policy in the city. My paper will focus on an important center of exchange between these groups: the Bauhof Handicraft Collective (Bauhof Handwerkskollektiv). Run by members of the squatter movement, the Bauhof provided a place where non-professionals could learn basic construction skills and techniques, and thus undertake “rehab-squatting.” For professional architects, such collectives, along with squats themselves, provided opportunities for experimenting with new and innovative approaches like community-based design and adaptive reuse. Examining archival materials related to the Bauhof as well as alternative architectural publications, including the journal Arch +, I will consider how politically-engaged architectural practices were “popularized,” both within the rehab squatting community and in professional circles, for example as part of the 1987 International Building Exhibition.

HGCEA’s annual dinner at CAA was held on February 14 at the Scandinavia House and attended by sixty members. The event this year honored the service and scholarly accomplishments of Françoise Forster-Hahn and Reinhold Heller upon their recent retirement from teaching. Their careers and influence were remembered in talks by Steven Mansbach and Allison Morehead, and a poem by Marion Deshmukh.

The results were also announced for the first annual HGCEA competition for best recent essay by a member who has received their Ph.D. within the past five years. Winners chosen by the Board were:

First prize:

Pepper Stettler, “The Object, the Archive, and the Origins of Neue Sachlichkeit Photography” in the journal History of Photography, August 2011.

Honorable Mentions:

Amy K. Hamlin, “The Conditions of Interpretation: A Reception History of The Synagogue by Max Beckmann,” in nonsite.org, October 2012.

Shira Brisman, “Sternkraut: The Word that Unlocks Dürer’s Self Portrait of 1493,” in the exhibition catalog Der frühe Dürer, Nürnberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 2012.

HGCEA Emerging Scholars

Chair: Keith Holz (Western Illinois University)

Over the past several years the Historians of German and Central European Art and Architecture have sponsored

sessions offering an opportunity for young scholars to share their work in progress with a professional audience. We aim to enrich the discourse within the field of German and Central European art history by encouraging a new generation of researchers. This year’s session presents new research informed by critical thinking on Romantic landscape paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, printmaking and printed currency during the years of Germany’s hyperinflation, and on the historiography of twentieth-century architecture in Poland.

“The Eye and the Hand: Caspar David Friedrich and the Organic Instruments of Artistic Creation'”

Nina Amstutz, University of Toronto

“TIn the 1820s, Caspar David Friedrich painted several anthropomorphic landscapes. Two such paintings, I argue, take the eye and the hand as their subjects. These organs are not painted in the likeness of the human body; they are metamorphosed into landscape. Eyes and hands are the conventional instruments of the imagination, and are often emphasized in self-portraiture. Their potency as symbols of creation is linked with their religious usage as emblems of God’s creative intervention. Friedrich reduces the traditional Christian iconography of the eye and hand to pure landscape, suggesting a discovery of God’s benevolent eye and divine handiwork in the wonders of nature. But these paintings also read as personal reflections on the status of eyes and hands in the creative process. Looking to analogies between the body and nature in Romantic nature philosophy, I contend that Friedrich conceptualizes the artist’s activity as an earthly equivalent to divine creation.

“Impressions of Inflation: Prints, Paper, and Prices in Germany, 1918-1923”

Erin Sullivan, University of Southern California

During the years of rampant inflation in Germany, the atmosphere of economic anxiety encouraged a boom in print

production. The inflation is visible as subject in prints by artists including Max Beckmann and George Grosz, and in popular press illustrations. But its traces are also present in the materials and the marketing of graphic works, as prints were increasingly promoted for their potential exchange value. This paper will explore these traces, and consider them next to characteristics of the ever-expanding supply of paper money, or Inflationsgeld. Prints and paper money shared attributes that became problematic in the context of inflation: both were “mechanically” reproduced, and their perceived value was tied to their relative rarity. Both also employed different strategies to affirm faith in the abstract, rather than actual, value of printed paper. The graphic arts, therefore, offer a unique visual and material archive of the inflation years.

“Historical Overhangs: Problematizing Cold War Era Temporal Frameworks in Polish Architectural History”

Dr. Anna Jozefacka, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

Historians of Eastern and Central European twentieth-century art and architecture who investigate the influence of politics and ideology on such disciplines routinely adapt their work to the well-established pre-war / post-war division of historical time. Validated by the mayhem of World War II, underscored by the establishment of communist regimes, and codified by Cold War era politics, such a politically based compartmentalization of historical time weighs heavily on the art and architectural history of this region. The paper uses the development of twentieth-century Warsaw to investigate the validity of that division and debate its consequences for art historical inquiries. Contrary to many studies of Warsaw’s post-World War II rebuilding, this investigation positions the city’s recovery efforts within a broader temporal framework that takes into account the prior thirty years of architectural and urban design effort to transform Warsaw into a capital city for the emerging modern nation state.

Central Europe’s Others in Art and Visual Culture, Panel I

Chair: Brett Vanhoesen, University of Nevada, Reno, and Elizabeth Otto, State University of New York at Buffalo

From Charlemagne to Schengen, the physical borders of Central European nations have been the subjects of constant dispute. Equally as fraught are the complex debates that have raged around notions of national and individual identity, which have been formed through such concepts as race, ethnicity, nation, temporality, religion, gender, and sexuality. These constructs have been powerfully solidified in visual representations. The papers for the panel “Central Europe’s Others in Art and Visual Culture” exemplify new approaches to concepts of the Other and related ideas of insiders and outsiders in representations from the Middle Ages to the present. Contributors will address discursive arenas and visual cultures that reflect the influence of trade, crusades, colonialism, post-coloniality, and tourism as they helped to form images and ideas of Others. Some of our panelists explore visual culture in relation to subtle and overt challenges to established institutions, structures of inclusion and exclusion, or conventional power dynamics. A number of the papers in this session rethink tropes of particular Central European identities and investigate how supranational constructs such as race, ethnicity, religion, gender, and sexuality were supported or challenged in visual representations of nation or Volk. Lastly, this panel will examine how visual materials enabled those considered marginal to engender agency through subcultures or other sites of resistance. Above all, we hope that this panel will provoke a broad spectrum of rich, rigorous engagement with notions of Othering across geographical and temporal boundaries in the Central European context.

“Central Europe’s Others, Now and a Thousand Years Ago: ‘The Exhibition Europe’s Centre around A.D. 1000′”

William J. Diebold, Reed College

“The exhibition Europe’s Centre around A.D. 1000,” on view from 2000 to 2002 in major museums in Germany, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, used visual and verbal expressions of otherness to define a central European identity. The exhibition emphasized the similarities between the present and the Middle Ages and argued that central Europe was unified around the year 1000 in ways that were remarkably similar to the kind of unification that was perceived to be taking place at the time of the exhibition, in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Because the exhibition did not take the expected position that the medieval past was other, it needed something else against which to define its view of central Europe. It found this crucial other in the non-Christian peoples of high medieval Europe: the Jews and the various groups that had not been converted to Christianity.

“Site/Sight of Alterity: Albrecht Dürer’s The Men’s Bathhouse of c. 1496”

Bradley J. Cavallo, Temple University

Despite its network of intersecting erotic gazes, no sustained attempts have been made to interpret Dürer’s “The Men’s Bathhouse” in the context of early-Modern gender normativity, its Other, or their regulation. Dürer’s print addresses these issues ambiguously by presenting a homo-social setting imagined as the site/sight of a homo-sexual desire that must conceal itself under the cover of inaction. His idealized naked males can look but can’t act on their desires because of their awareness of the unobtrusive act of surveillance performed by a clothed figure behind them. Overpowering them into stasis, his gaze analogizes that of a society desirous to prohibit sexual acts and hence maintain prescribed sexualities.

As depicted by Dürer, passive coercion in the form of acknowledged observation governs bodies best by encouraging them to regulate themselves, aware as they are of the gaze but not when, where, or how they might be inspected and judged.

“Savages on Display: The European Peasant and the Native North American at Central European Fairs in the Nineteenth Century”

Rebecca Houze, Northern Illinois University

World fairs and regional exhibitions were important venues in nineteenth-century Central Europe for expressing national identity. Ostensibly organized as celebrations of industry and empire, these events showcased the contrast between primitive and civilized in temporary pavilions and in exhibits of applied arts. By the 1890s ethnographers on both sides of the Atlantic, fueled by cultural anxiety about vanishing traditions in the face of industrialization as much as by the spirit of scientific inquiry, constructed elaborate villages demonstrating lifestyle and ceremonial practice from Moravian village weddings to Kwakiutl potlatches. This paper suggests that the Central European fascination with the Native North American was a response to industrialism and to the rise of nationalist movements in the late nineteenth century, and begins to explore a transatlantic dialogue, in which the image of the European peasant likewise became a surrogate for American ideas about tradition, immigration, and civilization.

“Otto Dix’s Jankel Adler and the Materiality of the Eastern Jew in Weimar Culture”

James A. van Dyke, University of Missouri-Columbia

This paper will consider a portrait painted in 1926 by the German artist Otto Dix, one of the most provocative and prominent artists of his day. In so doing, it will reflect upon what this particular picture contributes, on the one hand, to our understanding of the role of the Other in the constitution of Dix’s subjectivity and public image. On the other, the paper is intended to draw attention to the ambiguous, perhaps ironic presence of (anti-Semitic) stereotypes in, rather than simply against, Weimar Culture. The picture in question is Dix’s portrait of Jankel Adler, a Polish Jew who lived and worked as a painter in the Rhineland after the First World War and until his emigration after the formation of Hitler’s government in early 1933. Best known for his paintings of Jewish types and customs, Adler was a prominent figure in the avant-garde circles in Düsseldorf and Cologne.

“The Roma Pavilion: Contemporary Art and Transnational Activism”

Brianne Cohen, Université catholique de Louvain

This paper analyzes the Roma Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale (2011). Entitled “Calling the Witness,” the exhibition staged a stream of live “testimony” by artists, filmmakers, social workers, political activists, art historians, and more in order to interrogate the stateless position of Romani peoples today. Perhaps more than any minority in Central Europe, the Roma have been particularly demonized in the last decade as cultural outsiders. The pavilion assumed a contestatory symbolic role within the Biennale’s nationalistic structure.

Located at the UNESCO headquarters in Venice, “Calling the Witness” was also illustrative of a move away from nation-state-based cultural sponsorship towards other transnational humanitarian, legal, and social-activist models. How may such NGO-like models enliven visual-symbolic resistance to cultural Othering in Central Europe? What are some of the limitations of this shift in contemporary art? Such analyses are critical at a time of increasingly fluid borders and sociopolitical uncertainty in Europe.

Commentator: Maria Makela

Central Europe’s Others in Art and Visual Culture, Panel II

“A Black Jewish Astrologer in a German Renaissance Manuscript”

Paul H. D. Kaplan, Purchase College, State University of New York

Among the thousands of images of black Africans in pre-1800 European art, the depiction of a person of color in the act of writing is extremely rare. This paper explores a 1520 miniature by the Nürnberg artist Hans Hauser, an author portrait of the Jewish astrologer Sahl ibn Bishr (fl. ca. 820) which precedes one of his treatises. Hauser, probably at the behest of his patron, Elector Joachim I of Brandenburg, depicts Sahl – pen in hand and spectacles perched on his nose – with emphatically dark skin and African features. This unique image must reflect the influence of Joachim’s brother, Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg. Albrecht’s devotion to and promotion of two black African saints (Maurice and Fidis) resulted in many Christian images of Africans, but Hauser’s painting, of a Jew who wrote in Arabic for Muslim patrons, represents an unusual extension of this interest in Africans into the secular realm.

“Czech, Slovak, and Rusyn: Nation-building in First Republic Czechoslovakia”

Karla Huebner, Wright State University

With the founding of Czechoslovakia in 1918, this “multinational nation-state”—inhabited by Czechs, Slovaks, Germans, Jews, Rusyns, and many other less numerous ethnicities–needed to create an identity both internally and abroad. However, a major reason for bringing Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia into the new state was in fact the existing tension between Czechs and Germans, which prompted Czech nation-builders to seek a Slavic majority. Who, then, was considered Czechoslovak? How would the new citizens be portrayed in visual culture? This paper examines how Czech and Slovak periodicals represented Czech, Slovak, and Rusyn women during the First Republic and how Czech periodicals gradually but increasingly began to show Slovak and Rusyn women as Other, contrasting with an urban Czech ideal of a fashionable, active, efficient young woman. While remaining respectful, these representations show a growing recognition of difference and the Czechs’ move away from a sense of idealized pan-Slavic unity.

“The Outsider’s Vision: Bohumil Kubišta as Social Critic”

Eleanor Moseman, Colorado State University

The Czech artist Bohumil Kubišta (1884-1918) represents a self-imposed outsider fixed on exposing the tensions of class and ethnicity in Habsburg Prague, where Czech- and German-speakers compete for cultural, industrial, religious and political power. Kubišta’s paintings and writings reveal his engagement with the impact of modernity on social structure and the utopian view of art’s role in social progress, a stance not fully attainable without adopting the position of outsider. Steeped in Marxist philosophy, Kubišta targets capitalist mechanisms of access and labor, set against the religious underpinnings of bourgeois society, which reinforce the imperial power of social elites. While economic need dictated his enlistment in the Habsburg navy, the seemingly contradictory status of a modern artist as imperial sailor actually provided Kubišta with the necessary distance to recognize and critique class and ethnic stratification in Prague as symptomatic of broader power structures reinforced by capitalist and imperialist domination.

“From Fiction to Fact: The Need to Document in Post-Yugoslav Art”

Nadia Perucic, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York

In Denmark, ideas of nationalism were perhaps never more highly charged than during the German occupation of World War II. To the leading modern artists of the period, at stake were not only notions of national identity and political belief, but also the very survival of culture itself. In response, the social-activist collective and eponymous journal Helhesten spearheaded cultural resistance in Nazi-occupied Denmark through a radical art that promoted ideas of community, experimentation, and Danish folk in opposition to the Nazi conception of Volk. This paper explores how Helhesten mobilized the chaos and fear brought about by the occupation to establish a new kind of countercultural movement that set the stage for post-war groups such as CoBrA. It also serves as a reassessment of the emergence of later twentieth-century avant-gardes as well as the way in which art history understands the exchange between national and international, and local and foreign.

“To Hell and Back: ‘Helhesten’ and Cultural Resistance in World War II Denmark”

Kerry Greaves, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York

Following the Yugoslav Wars of 1991-1995 and the breakup of the country into several states, the new political and cultural leadership established regimes that caused a general closing of society, different from the restrictions that characterized socialist Yugoslavia. Memories of the socialist past were suppressed, unsavory aspects of the present were ignored, and outsiders and other undesirables were marginalized. My paper focuses on Post-Yugoslav artists who, throughout the 1990s and 2000s, aimed to reverse this trend by recovering forgotten histories or highlighting contemporary issues that were censored by their new governments and the mainstream media. These artists often used extensive preliminary research as part of their method, leading to works with a documentary or journalistic format. I will show how, by adopting elements of reportage, artists aimed to position their artworks in opposition to the dominant public discourse in an effort to shape a more comprehensive and inclusive social reality.

Commentator: Steven A. Mansbach, University of Maryland

Picturing Urban Space in Central Europe since 1839

Chair: Miriam Paeslack, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

When the daguerreotype took Europe and the world by storm within weeks of its publication in Paris in 1839, a tremendously powerful tool for the urban imagination was born. While veduta- and street-painters had been meticulously documenting and spontaneously sketching the city in the earlier decades of the century, photography soon was able to capture motion and urban life. This opened up a whole new range of topics and issues in city imagery.

This panel investigates the cross-fertilization between 19th century city photography and urbanization in central Europe, for example in Berlin, Warsaw, Budapest, Vienna, Prague and or other Central European cities. It addresses the “pictorial turn” in urban representation that was triggered by the arrival of photography, and its repercussions for other visual media. More specifically, it asks about the different visual languages, expectations, and functions of urban representations found in diverse media – photography and film, but also drawings and paintings – since the 1840s. How have these different media impacted our perception of the city, and what were their respective means of “constructing” the city? How did urban growth, the urbanite’s sense of identity, and the image of the city interact? How did the urban image’s evolution relate to urban development?

Visual and architectural historians, human geographers, and artists are encouraged to submit proposals for presentations studying the spatial, structural, social and/or cultural encoding generated by urban imagery. Such studies could focus, for example, on the way that urban imagery addresses relationships of space and time/history or how national identity figures into such imagery. Proposals comparing two or more cities, and urban imagery from the 19th through the early 20th centuries respectively are welcome, as are proposals by artists working with historic imagery or relying on historic urban imagery as a point of reference.

“The Invisible City: Architectural Imagination and Cultural Identity Represented in Competition Drawings from Sibiu 1880-1930”

Timo Hagen, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg

Sibiu, the European Capital of Culture in 2007, was the center of Transylvania for centuries, and around 1900 characterized by its population’s cultural diversity. At this time the townscape was changed substantially by a wave of new building projects. In addition to the buildings actually built, drawings submitted to architectural competitions provide a deeper insight into contemporary architectural discourses: often revised or dismissed, these sketches form the image of a city existing only on paper. In my presentation I explore principles, which led to the selection of the drawings for those buildings that were eventually executed. I analyze how architects tried to affect decisions through elaborate drawing designs, highlighting the buildings’ aesthetic value and the associated concepts of cultural identity. The broad spectrum of building types shed light on the diversity of competing cultural identities in Sibiu during the period, while drawings reveal how visual representations helped communicate such identities.

“Picturing the Nation: The Multifaceted Image of Hungary at the 1896 Millennium Exhibition in Budapest”

Miklós Székely, Ludwig Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest

This presentation discusses and critically reflects on the meaning and importance of ephemeral exhibition architecture at the 1896 millennial festivities in Budapest, Hungary through its photographic representation. The lecture aims to show how politics influenced not only the architecture of the exhibition venue – a city within the city – but also its photographic representation, which was used to convert it into a national lieu de memoire. Pavilions were dedicated to express the nationalist politics of the re-emerging Hungarian political class, which aimed at reinstalling the country’s image as independent, economically and politically strong European nation. For that purpose, surviving monuments were re-erected in ephemeral versions for the millennial festivities. This exhibition and its pavilions was also one of the last examples of historicism-based cultural policy at the turn-of the century. After 1900, the Hungarian pavilions in universal exhibitions emphasized the vernacularism based modernist side of Hungarian culture.

“Architecture, Monuments, and the Politics of Space in Kolozsvár/Cluj”

Paul Stirton, Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture

In 1902 János Fadrusz’s equestrian statue of the Hungarian Renaissance king Matthias Corvinus was unveiled on the main square in Kolozsvár, Transylvania, marking out this central locale as a distinctively Hungarian space in a region with an increasing majority of Romanians. It also inaugurated a competition for cultural dominance of the urban landscape by rival ethnic groups that lasted throughout the inter-war period (when Transylvania was ceded to Romania), the Communist period, and even after 1989. This paper addresses both the transformation of the city squares and their interpretation through ritual celebrations and photographs that served to focus attention on certain features and to heighten their symbolic importance.

“Urban Space as a Visual-Haptic Experience: Stereoscopic Views of German Cities, 1880-1910”

Douglas Klahr, University of Texas at Arlington

In the second half of the nineteenth century, stereoscopic views of European cities became immensely popular, and those of German cities dominated the market in Central Europe. Stereographs often delivered sensations of depth that were haptic in intensity, a result due not merely to binocular optics, but also to the kinesthetic relationship between viewer and device. The stereoscopic experience therefore was phenomenological, establishing a realm of psycho-corporeal space unlike any other visual medium, in which the sensation of depth was corporeal rather than intellectual. Stereoscopy therefore seemed ideally suited to provide an illusion of depth, which is the sine qua non in pictorial depictions of urban space, yet consistently delivering this illusion was problematic. This talk addresses the challenges that stereographers encountered when photographing urban spaces, which lead them often to depart from iconic images of German Cities that were marketed in widely-distributed viewbooks during the same period.

“Picturing Contested Space and Subjectivity in the Urban Milieus of Budapest and Vienna”

Dorothy Barenscott, Simon Fraser University

Examining the powerful role that urban spaces have played in the social imaginary of nation and Empire, this paper explores the new media forms of photography and film as they appeared at key historical moments in the interconnected development of Budapest and Vienna’s urban character in the fin de siècle period. Arguably, these new media forms operated as a powerful visual patois that celebrated and exposed the most pedestrian and de-institutionalized visions of a modern world—ephemeral and fleeting moments that competed with and broke the illusion of grand monuments dedicated to abstract concepts of nationhood and citizenship. What were the new spaces produced by photography and film in the dual capital cities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire? And how did they affect the difficult histories and distinct perceptions of time-space, but also the competing theories of modern subjectivity and picture-making, that would emerge out of both places by WWI?

HGCEA Emerging Scholars

Chair: Timothy O. Benson, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

“Viva Durero! Albrecht Dürer and German Art in Nueva España”

Jennifer A. Morris, Princeton University

In the early modern period, settlers and missionaries from the farthest reaches of Europe traveled to the Americas with the goal of converting the New World into a Christian paradise. With them came a number of artworks that circulated widely and served as prototypes for the “hybrid” art forms of colonial America described by George Kubler and others. This paper examines the presence and impact of German art in the New World in particular, using the transmission and imitation of Albrecht Dürer’s prints in Nueva España as a model for the interaction between Indo-American and German art in New Spain and hence for the reception of Central European styles in colonial art at large. By considering the afterlife of Dürer in the New World, this study demonstrates that Central European art was pervasive and continuously influential in the Americas, serving important artistic, religious, and political functions in a spiritual battlefield.

“‘Opium Rush’: Hans Makart, Richard Wagner, and the Aesthetic Environment in Ringstrasse Vienna”

Eric Anderson, Kendall College of Art and Design

In 1871, critic Wilhelm Lübke characterized the paintings of Viennese artist Hans Makart as “gemalte Zukunftsmusik.” Lübke intended no compliment. Drawing a comparison to composer Richard Wagner, Lübke denounced Makart’s art as mere surface, lacking intellectual or moral value. Both Wagner’s “colossal masses of sound” and Makart’s “nerve-tingling colors,” he wrote, offered only a stupefying narcosis for the sensation-addled parvenu of the Ringstrasse: “an opium rush, received through the ear or the eye.”

Around 1900, the Viennese critic Ludwig Hevesi offered a striking reassessment, celebrating the decorative, psychologically immersive character of Makart’s paintings, and especially his decorated interiors, as a sophisticated and elegant means of escaping the crises of modernity. Taking Hevesi’s remarks as a starting point, this paper will reconsider the relationship between Makart’s interiors and Wagner’s concept of immersive experience, taking into account links to Aestheticism, the Secession, and fin-de-siècle theories of mental life that informed Hevesi’s analysis.

“Architecture on Moscow Standard Time”

Richard Anderson, Columbia University

Focusing on the 1930s, this paper explores architecture’s relationship to the Communist Party’s politics of time. After the competition for the Palace of the Soviets of 1932, Party officials prescribed the use of “both new techniques and the best techniques of classical architecture” in future projects. Although this event has long been interpreted as a negation of the agency of the avant-garde, this paper presents the architectural debates that followed as symptoms of the chronotope—the time-space—in which they unfolded. Concretely, it traces the ways that leading architects—Moisei Ginzburg, Aleksandr Vesnin, Ivan Leonidov, among others—responded to the proposition that a progressive, socialist architecture could arise only from the “critical appropriation of architectural heritage.” By attending to rarely-discussed projects and texts, this paper shows how Soviet architects articulated a theoretical program that would position socialist architecture ahead of the West, paradoxically, by turning to the past.

HGCEA at CAA 2011 New York

The Display of Art and Art History, From the Premodern to the Present

Chair: Karen Lang, University of Southern California

Alois Riegl’s engagement with Late Roman antiquity in Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts stimulated a new art-historical method of relative values. Aby Warburg’s experience as a student in Florence of Italian quattrocento art resulted in a novel approach to the “afterlife” of antiquity. The young Wilhelm Worringer, contemplating medieval cast reproductions in the Trocadéro, chanced upon the sociology professor Georg Simmel; their meeting sparked the conception of Worringer’s Abstraction and Empathy. Despite attention to foundational moments such as these, we have yet to learn in depth and across time about interrelations between the exhibition of art and the history of art history as a disciplinary practice. This panel draws on exhibition histories and historiography to address the multidirectional and reciprocal ways the display of art and art-historical methodologies have shaped each other in Germany and Central and Eastern Europe, from the premodern to the present. Previous scholarship has focused on the museum and the university as art history’s “two cultures.” This panel explores relations between exhibition history and art history to open a new stream of research.

“Virtual Display: The Role of Drawing in the Early Modern Art Collection”

Susan Maxwell, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh

Works on paper did not became part of the culture of collecting until the late sixteenth century, but even then, patrons valued them differently than in contemporary practice. For example, Duke Philipp of Pommern-Stettin had his art agent commission drawings that documented works of art in the ducal collection in Munich rather than commissioning new works himself. When the drawings were assembled into albums, Philipp possessed a virtual re-creation of his rival’s art collection. In 1565 Samuel Quiccheberg wrote the first theoretical text on the organizational structure of the ideal museum for Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria, who created the first Kunstkammer, or ducal art collection, north of the Alps. Quiccheberg’s theory provides insight into how these patrons may have valued drawings and prints. This paper analyzes primary sources to determine whether drawing was viewed as a creative endeavor or a tool in organizing and possessing knowledge within a collection.

“Pattern Book, Museum, and Ethnographic Village: Intersections of Art History and Ethnography in Austria-Hungary”

Rebecca Houze, Northern Illinois University

The development of art history coincided with that of ethnography in the Dual Monarchy, Austria-Hungary, at the end of the nineteenth century. The relationship of the two fields at that time was especially evident in the diverse modes of display employed in their publications and exhibitions. Illustrated albums from the 1860s and 1870s, with luxurious color-lithograph printed plates, catalogued embroidery and woven textile designs from various sources. These pattern sheets, produced for industrial designers, foreshadowed Alois Riegl’s theoretical treatises on ornament and folk art based on his own observations of textiles. At the same time, installation practices from the realm of fine and industrial art lent themselves well to ethnographic comparisons by scholars such as Michael Haberlandt and János Jankó in the 1890s. This paper considers three examples—the pattern book, the comparative installation, and the ethnographic village—in an effort to better understand the intersections between them.

“An Art History of the ‘Most Neglected’: Art History and Ethnology in German-Speaking Scholarship”

Priyanka Basu, University of Southern California

One important consequence of assembling the data of the earliest surveys of art history was that lacunae became visible. Art historians in the following generations elevated these unknown areas and periods to objects of study, many claiming to renounce previous norms and personal taste and give attention to the previously marginal. One of these gaps was occupied by “primitive” art, encountered in ethnological studies and museums and which gained visibility in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries along with other nonclassical artifacts and prehistoric art. This paper deals with a number of theorists and historians who attempted to determine the relationship of these to art history, as part of a broader enterprise of negotiating disciplinary boundaries and methodologies. It attends also to the representation of these objects in publications, sometimes as reproductions of fragments of patterns and ornament, from which art-historical beginnings and ur-motifs were extracted.

“Expansion of the Discursive Field: Harald Szeemann’s documenta 5 (1972)”

Ursula Frohne, University of Cologne, Germany

Arnold Bode’s documenta sought to reconnect Germany to international avant-garde positions in the aftermath of World War II. In the climate of the Cold War, he reestablished the autonomous, abstract, and form-genealogical idea of art within the art-historical canon of medium specificity and originality. By contrast, Harald Szeemann’s concept for documenta 5, with its programmatic “inquiry of reality—image worlds today,” presented a heterogeneous ensemble of visual artifacts from diverse cultural contexts. Emphasizing the notion of “parallel visual cultures,” Szeemann broke with the modernist principle of the artwork’s autonomy and the traditional order of images. This paper examines Szeemann’s transformation of exhibition display and its historiographic, cultural, and epistemological orders. It argues that documenta 5’s scenography anticipated the new horizon for art history’s methodological expansion toward Bildwissenschaften (science of the image).

“Raphael and Stalin in Dresden: Art, Display, and Ideology”

Tristan Weddigen, University of Zurich

On Stalin’s instructions, a list was made of two thousand artworks to be seized in Germany as trophies for a World Museum of Art. The most sought after was Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. In 1945 the Trophy Brigades found Dresden destroyed, but they discovered the hidden art depots. Two hundred thousand objects were sent to the Soviet Union, especially to the Pushkin Museum. These formed a secret museum within the museum, and the spoliations were denied. After signing the Hague Convention in 1954, and following Khrushchev’s De-Stalinisation, the Soviet Union began to return this booty (estimated at $2.5 million) to the West. The repatriation of the Dresden Picture Gallery in 1956 was accompanied by massive propaganda in which the work of the Trophy Brigades and the Soviet art restorers was touted as a rescue operation from the barbarism of the Nazis and the Allies. The paper investigates how the Stalinist aesthetic legacy still defines Dresden’s cultural identity.

HGCEA Emerging Scholars Session

Chair: Mitchell B. Merbeck, Johns Hopkins University

“The ‘Ghostly Semblance’ of the Modern: Deformation and Transformation of Images in Der Blaue Reiter”

Charles Butcosk, Princeton University

The 1912 publication of Der Blaue Reiter presented an almanac of essays and works of art as eclectic as the book’s eponymous exhibition society. The range of works reproduced in the book is vast, including not only paintings by Pablo Picasso and Paul Cézanne but also Iberian masks, Gothic prints, Egyptian shadow puppets, and children’s drawings. These latter images, often cropped to the point of being unreadable fragments and seeming to float enigmatically in and around the text, defer and mediate the works they reproduce, often reducing them to art-historical emblems. This paper examines the transformation and deformation of images in Der Blaue Reiter and their relationship to figurations of the past in essays by Franz Marc and August Macke. In so doing, it reconsiders the relationships between painting and the present in a project that was at the core of Der Blaue Reiter.

“Painting in Arcadia: Kirchner and Male Friendship, 1914–17”

Sharon Jordan, Institute of Germanic and Romance Studies, University of London

Throughout the vast literature on the German Expressionist artist Ernst Kirchner, the psychologically devastating experience of service during World War I is regarded as one of the defining aspects of his biography. This paper sheds new light on this crucial period by examining images depicting the artist’s fleeting friendship with Botho Graef, a classical archaeologist and art historian, which coincided with the duration of the war. An iconographic analysis of these artworks reveals the foundation of the men’s friendship in their mutual engagement with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche and shows how Graef’s devotion to the ancient Greek tradition of pedagogical male friendship proved inspirational. By considering the interrelationship between Kirchner’s extreme mental difficulties and the war’s ultimate ruination of this vital friendship, this discussion further expands our understanding of the artist by offering additional interpretations for self-portraits relating directly to his profound period of crisis in 1915.

“Some Uses of Photomontage in Soviet and German Periodicals in the 1930s”

Katerina Romanenko, The Graduate Center, City University of New York

This paper questions the persisting perceptio that Stalinist and Nazi regimes rejected photomontage because of its association with modernist experimentation and with the political Left by tracing some of the ways the medium was appropriated for the totalitarian modes of expression associated with the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. The discussion reveals that for magazine designers, photomontage was mostly a technical tool enabling the organization of visual material in a dynamic yet also concise and economic manner. This suggests that while both regimes rejected the radical language of photomontage characteristic of the 1920s, the technical and visual flexibility of the medium, coupled with photography’s documentary quality, were regarded as useful despite the controversial associations of the medium. Various uses of photomontage throughout the decade, using examples from periodical press of the 1930s—USSR in Construction, Krestianka, Rabotnitsa, Illustrierter Beobachter, Frauen Warte, and others—are compared and analyzed.

Transformation Reconsidered: ‘Utopias’, Realities and National Traditions in post-1989 Central Europe

Chair: Andrzej Szczerski, Jagiellonian University, Cracow

Twenty years of post-Cold War transformation in the Central European region had been marked by recourse to lost identities and renewed interest in national histories and traditions. Concurrently, new questions have been posed regarding regional experience, including whether remnants of the communist system and the incoming capitalist globalization can provide a new socio-political and cultural model for contemporary Europe. In both instances, retro- and prospective ones, art, artists, and critical/historical discourse play a crucial role in forging new and questioning old identities. The session will analyze attempts to regain or reinvent national and individual histories, lost or destroyed during the Iron Curtain era. It will also look at the idea of remembrance about the communist ‘utopias’ and realities, their relevance, persistence and rejection within contemporary societies, as reflected in current art production as well as historiography. Since attitudes towards the recent past are highly politicized and often mutually exclusive, the question will be asked to what extent art, art history, and criticism can provide a platform for negotiations within the emerging civil society. The session will also consider the problem of how the post-communist transformation has been perceived as a lived reality, with its own cultural models and hierarchies.

“Work with Drawers, Slide Trays, Files, and Boxes!”

Georg Schoellhammer, Springerin, Hefte fur Gegenwartskunst

Twenty years after 1989 neo-avant garde and post conceptual art from the so called Former East is still confronted with a stereotypic reception elaborated in the early 1990s. Already by then the Western efforts of presenting a comprehensive reading of the avant gardes that had worked behind the Iron Curtain was palimpsested by its reception as a mere mirror of Western art practices. The paper will look at the histories of exhibitions of Eastern European art in Western institutions vis-à-vis materials that still hide away in private archives in Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania. Its aim is to show how these archives have enabled communication, and how their forms and formats have themselves influenced the macro-structure of some of the exhibitions. Question will be asked about the strategies available to counter hegemonic subordination to the rules of the Western canons.

“Continuity of Art Informel and Artistic Self-Assertion in the GDR after the Cold War”

Sigrid Hofer, Philipps-Universitat Marburg

Since the nineteen-fifties numerous artists gathered in Dresden to cultivate forms of abstraction and to developed Art Informel. While Informel Art in the West was considered to have degenerated into a fad only after a few years it maintained its actuality in the East for several decades and was not even abandoned after the Wall came down. In the years of state-ordered Socialist Realism the decision for Informel was at the same time an expression of latent resistance. Therefore it seems that this distinctive approach influenced the artist’s self-image in a more crucial way than this appears to be the case in non-obstructive contexts. The presentation will investigate whether and to what extend new impulses brought change to Art Informel after 1989, and especially how adhering to tradition and continuation was a necessary condition for artists to affirm their own identity.

“‘The Future Is Behind Us'”

Edit Andras, Hungarian Academy of Sciences

In the turbulent period of transition, in the ex-East Block, contemporary art faces utopias in two ways, artists revisit the past searching for the moment when utopias went wrong, or, they eagerly look for new utopias in the condition of global capitalism, analyzing and adapting the enormous heritage of utopian thinking of the region for a disillusioned time, obsessed with dystopias. The paper is to peel off the layers covering the origins of some basic utopias, the ruins and remnants of which are still in our midst. The paper focuses on works which redirect the attention to the need of a retrospective analytical work, a kind of therapy of wounds and failures of the past. Some artists are eager to take responsibility of conscience of the societies that tend to forget their dreams of a better future. The presentation concentrates on video and conceptual art.

“The Possibility of the Postnational in Contemporary East European Art”

Maja and Reuben Fowkes, Translocal.org and University College London

The art history of the countries of Eastern Europe before 1989 was written, according to Piotr Piotrowski, more on the basis of ‘state apparatuses’ than ‘ethnicity’. Immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the afterglow of the internationalist ideals of socialism could still be felt, while the desire for free and open communication across state, ideological and national borders was predominant. Subsequently, the first post-communist decade saw the rise of identity politics, during which a national prefix became an obligatory addition to survey exhibitions of contemporary art in the countries of the former Eastern Blok. This paper discusses the changing understanding of the national in contemporary art since the End of Communism and the shift of interest during the second post-communist decade away from issues of identity in both its national and regional formulations towards an exploration of the possibilities of a post-national sense of belonging.

“The Situation: Contemporary Art Practice in the Post-Cold War Era”

Elizabeth M. Grady, Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York

The contemporary moment is rife with “posts”: Post-Cold War, post-Communist, post 9-11, post-colonial, and even post-national. Blogs embody decentralized communities of identity-shifting “post-ers” who together determine the parameters of everything from what’s hip to the next revolution, often offering a faux-reality of democratic access and collectivist practice. But what is left when we’re offline? How do we come to terms with the reality of our decidedly non-ideal or falsely idealized cultural, social, political, and even material positions? And what role does art play in exposing or perpetuating this disjuncture between ideology and reality, virtual and real existence, mediated and actual experience? This paper will demonstrate the current efforts of artists to expose the disjuncture between the ideologically loaded virtual and media-driven models of reality that govern our collective cultural consciousness and the possibilities for individual agency and personal freedom of movement outside these powerful but ultimately hollow models for living.

Forging California modernism: Central European émigrés on the West Coast between 1920 and 1945

Chair: Isabel Wünsche, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Jacobs University, Bremen, Germany

At the beginning of the twentieth century, California was a cultural melting pot in which the local traditions of Native American, Hispanic, and Asian cultures mixed with the diverse influences of European modernism. The multitude of cultural influences as well as the relative immaturity of the California art scene attracted numerous European émigré artists and intellectuals and enabled them to become a driving force in introducing and establishing modernist art and design. This session will discuss the contributions artists, architects, photographers, and filmmakers from Germany and the former Habsburg Empire made to the emergence of modernism in California. Particular emphasis will be on the role European émigré architects played in shaping modernist architecture and design, the incorporation of modernist idioms into photography, the development of hybrid photographic styles that merged European modernist aesthetics with the American social documentary approach, and the influence that Central European avant-garde filmmakers gained upon Hollywood.

“A Position ‘Neither Here nor There’: Hansel Mieth’s and Otto Hagel’s California Photographs, 1928-1936”

Dalia Habib Linssen, Boston University

Arriving in San Francisco at the outset of the Depression, German-born photographers Hansel Mieth and Otto Hagel began chronicling a California they experienced as both active participants and perceptive observers. Forced to pick crops and work in factories, this émigré pair produced a distinctly modernist and politically-minded body of photographic work between 1928 and 1936. In directing their cameras toward those with whom they shared their struggles, including migrant laborers, Chinatown residents, and maritime workers, Mieth and Hagel skillfully negotiated the boundaries between worker and photographer, immigrant and resident, and European and American stylistic approaches. They developed a hybrid photographic style that merged the aesthetics of European modernism with the humanism of American documentary practices. Though known mostly for their photojournalistic work, I introduce Mieth and Hagel’s early contributions to show how their work complicates and expands our understanding of 1930s California photography.

“Camera Infirma: John Gutmann in California”

Miriam Paeslack, California College of the Arts, Oakland/San Francisco

Berlin émigré John Gutmann arrived in San Francisco in 1933. Although he had been trained as a painter by German Expressionist Otto Müller and intended to use the camera only commercially, he became best known for his intriguing, subjective photographs of mid-century American culture. In California, he used photography not just as a means of income but as a documentary tool, revealing as much about the place documented as about the documentarian. This paper examines Gutmann’s use of photographic qualities as a language of signification; it asks about the visual indicators for displacement and how Gutmann’s photographs, shaped by the outsider’s perspective, contribute to the development of California modernism. I will discuss how Gutmann’s photographs fit into the aesthetic and cultural discourse of Northern California photography between Dorothea Lange’s social documentary approach and the f64 group’s meticulous sense of aesthetic and technique.

“The Photographs of Arthur Luckhaus and the New Architecture of Richard J. Neutra”

Ruben A. Alcolea, School of Architecture, University of Navarra, Spain

The series of pictures taken by Arthur Luckhaus in California in the first half of the twentieth century illustrates both the changing of American society as well as the turn to New Objectivity in photography. Arthur Luckhaus, a photographer unknown until today, was the official photographer of the early works of the well-known Californian and Austrian-born modernist architect Richard J. Neutra, who introduced the idea of integrating industry and the machine into the modern languages of architecture and spatiality. In my paper, I will show some of the recently discovered photographs by Luckhaus in the context of the transition from Pictorialism to New Objectivity in California and also discuss them in relation to the development of early modernist architecture in Los Angeles, especially the work of Neutra. I thus will establish that both Luckhaus and Neutra are key figures for understanding modern photography and architecture.

“Artistic Survival in Paradise: German-Speaking Architects in California after 1933”

Burcu Dogramaci, University of Hamburg, Germany

Two factors were significant for the success of German and Austrian émigré architects attempting to establish a new existence in California in the 1930s: a high level of flexibility and the ability to network. Fritz Block and Ernst Hochfeld quickly adapted to the new situation by temporarily taking up photography and stage design; Oskar Gerson and Liane Zimbler found their most important clients among the German-speaking émigrés on the West Coast. This paper will focus on the émigré networks in California and their importance for the exiled architects. I will discuss why émigrés commissioned other émigrés and examine the clients’ wishes with respect to the design of their private homes, including the desire to aesthetically relate their new surroundings to the European Heimat versus attempts to adapt local architectural styles.

“The Unlikely Director: Paul Fejös and the Hollywood Connection, 1927-28”

Dorothy Barenscott, Trent University, Canada

In histories of early Hollywood, the community of Hungarian filmmakers, directors, and moguls, who played a decisive role in American filmmaking from its earliest inception, remain among the most misunderstood of all Central and Eastern European émigré groups. This paper focuses on one such related figure, director Paul Fejös, and his brief yet meteoric rise to fame in 1927-28. After leaving positions in Hungary, Austria and Germany, Fejös arrived in America and produced a low budget avant-garde film that garnered broad critical acclaim and led to a lucrative contract with Hollywood’s Paramount Studios to begin producing what would be understood as “cross-over” films linking European and Hollywood filmic approaches, techniques, and philosophies. Through a discussion of Fejös’s professional background and projects, I will explore a range of modernist and avant-garde techniques often overlooked in the visual, narrative, and contextual elements that make up his category of Hollywood films.

Feminism and Modernity in Central Europe

Chair: Adrienne Kochman, Indiana University Northwest, Chair

The association between feminism and power, and modernity with patriarchal systems represents a set of long established binaries addressed years ago in Broude and Garrard’s Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany (1982). Women’s forays into modernity and the ‘art world’ were conditioned and/or filtered by male-dominated expectations concerning quality, productivity, the media with which they worked, and their relationship to women’s traditional roles as mothers, wives and partners. Recent research on women artists of Central Europe, including Germany, indicates that some of the values, morals and societal expectations around these issues were particular to the region as was perhaps the very concept of woman herself. Studies of collaborations by artist couples, women as patrons and artists, and women’s participation in artist groups are some of the frameworks around which their contribution is being explored as is the role of class, privilege and economics. Differences in labor demands between urban and rural environments, as well as gender identities encoded in the cultures of Catholicism, Judaism, Orthodoxy, Protestantism and Islam also affect concepts of woman and feminist artistic behavior. This panel focuses on the 20th century, from pre-World War I Germany and Austro-Hungary to the First Czech Republic, Weimar Germany and the G.D.R.. It includes methodological reappraisals of stylistic movements, the inscription of gender in modernist discourse and the redefinition of subject matter and themes traditionally appropriate for women artists to pursue.

“Paula Modersohn-Becker: the national, regional and the Modern”

Shulamith Behr, Courtauld Institute